Order has been restored:

Australia allows only human inventors

On April 13th, 2022, in “Commissioner of Patents v Thaler [2022] FCAFC 62”, on Appeal from: “Thaler v Commissioner of Patents [2021] FCA 879”, VID 496 of 2021, Honourable Chief Justice Allsop, and Justices Nicholas, Yates, Moshinsky and Burley of The Federal Court of Australia decided that the artificial intelligence system DABUS (Device for Autonomous Bootstrapping of Unified Sentience) CANNOT be mentioned as an inventor because the inventor must be a natural person.

The decision goes deep into the details of the statutory language, structure and history of the Australian Patents Act, and the policy objectives underlying the legislative scheme. This means that the court does not simply take the references to “person” to mean, definitively, that an inventor under the Patents Act and Regulations must be a human. However, in the light of the sources of law, the court finds it clear that the law relating to the entitlement of a person to the grant of a patent is premised upon an invention arising from the mind of a natural person or persons. Those who contribute to, or supply, the inventive concept are entitled to the grant. The grant of a patent for an invention rewards their ingenuity.

Regarding the consequences of allowing non-human inventors in the form AI, the court says: “In our view, there are many propositions that arise for consideration in the context of artificial intelligence and inventions. They include whether, as a matter of policy, a person who is an inventor should be redefined to include an artificial intelligence. If so, to whom should a patent be granted in respect of its output? The options include one or more of: the owner of the machine upon which the artificial intelligence software runs, the developer of the artificial intelligence software, the owner of the copyright in its source code, the person who inputs the data used by the artificial intelligence to develop its output, and no doubt others. If an artificial intelligence is capable of being recognised as an inventor, should the standard of inventive step be recalibrated such that it is no longer judged by reference to the knowledge and thought processes of the hypothetical uninventive skilled worker in the field? If so, how? What continuing role might the ground of revocation for false suggestion or misrepresentation have, in circumstances where the inventor is a machine?”

For the purpose of the proceedings, the parties agreed on the below facts:

- AI systems are implemented within machines and are programmed to simulate specific thought processes and actions of humans. Artificial neural networks are implemented within machines and self-organise to simulate the way in which the human brain processes and generates information. AI systems may incorporate, or be constituted by, artificial neural networks.

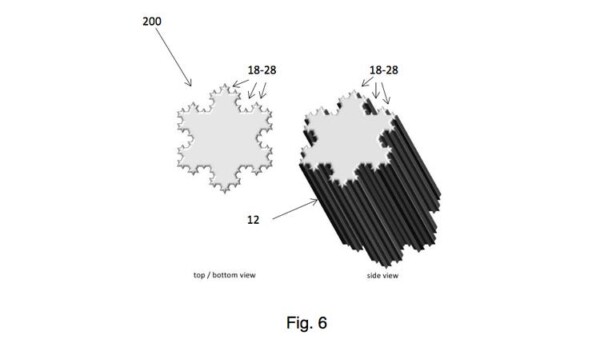

- DABUS is an AI system that incorporates artificial neural networks.

- The output of DABUS is an alleged invention the subject of the application.

- DABUS is not a natural or a legal person.

- Dr Thaler is the owner of the copyright in the DABUS source code, the owner of the computer on which DABUS operates, and is responsible for the maintenance and running costs of DABUS and the computer on which it operates.

- Dr Thaler is not the inventor of the alleged invention the subject of the application.

These facts finally enabled the court to conclude that Dr Thaler’s patent application did not fulfil Reg 3.2C(2)(aa) of the Australian Patents Act 1990, which requires an applicant to provide the name of the inventor of the invention to which a patent application relates.

Consequently, the legal practice in Australia is now in line with the legal practices in Europe and the U.S., where corresponding decisions have been taken by the EPO, UKIPO and the USPTO respectively.

Text: Joakim Wihlsson

Källa: Federal Court of Australia